Agallamh na Scoláirí

In the summer of 1745, Charles O’Conor of Belanagare (1710-1791), the Gaelic historian, scholar and prolific pamphleteer noted the imminent death of Dominic O’Duignan in his diary:

Iun 5 1745: … Dominic Ua Duibhgennáin, Seanóir Chloinne Gaodhal, d’fhagháil bháis ar a tseachtmhuin so. Bu hé sin mh’oide san Scuit-Bhérla, agus ba duine cráifeach, agus trócaire dha anmoin.

June 5 1745: … Dominic Ó Duibhgheannáin, an elder of the Gael, is dying this week. It was he who was my teacher in Irish, and he was a holy man, mercy on his soul.

The entry was in Irish, O’Conor’s native language, and composed in the traditional Gaelic hand which O’Duignan had taught to O’Conor decades before. The O’Duignans had been hereditary scholars and professional historians to the Gaelic nobility of North Connacht since the Middle Ages, and it was Dominic, the last of them, who had instructed the young O’Conor in the study of medieval Irish manuscripts. O’Duignan’s death marked a watershed, drawing to a close that tradition of hereditary scholarship. But upon O’Duignan’s death, much of the weight of that learned tradition fell onto the intellectually broad shoulders of Charles O’Conor. In the decades that followed, O’Conor emerged as the premier scholar of Irish language, literature and history, and the most important conduit in communicating their importance to the outside world. Most especially, he was a major force in facilitating the access of the Anglophone, Irish Protestant ascendancy to the riches of the Irish language. In doing so, he undoubtedly saw himself as preserving something of the Gaelic intellectual tradition in a time of crisis.

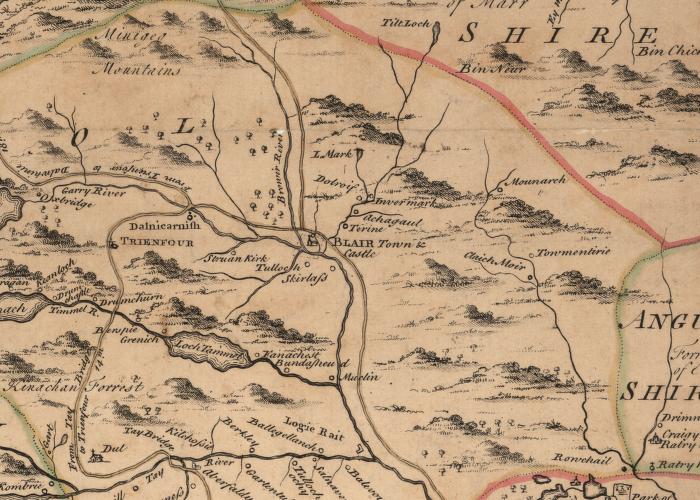

The second half the eighteenth century saw a parallel cultural crisis in Gaelic Scotland. After the defeat of the Jacobite Uprisings of 1745 and 1746, the Hanoverian state did its best to crush the Gaelic culture which had come to be associated so closely in the mind of the authorities with the Stuart cause. This effort on the part of the state was met by a small but intellectually driven cadre of Gaelic-speaking gentlemen (they were all men) who aimed to preserve and propagate their native language, by collecting her songs and ballads. The greatest of these was Rev. James McLagan (1728-1805), a native Gaelic-speaker from Highland Perthshire who for more than two decades was chaplain to the famous Black Watch regiment, seeing military action in America, Ireland and the Isle of Man. McLagan collected over 2,000 manuscript pages of Gaelic literary material throughout his lifetime and developed a knowledge of Gaelic literature, especially fiannaíocht literature, which was unrivalled in his own time. Although lacking O’Conor’s formal training in classical Gaelic scholarship, McLagan was undoubtedly the greatest Gaelic scholar in Scotland in the entire eighteenth century.

Remarkably, while McLagan was stationed in Ireland in the late 1760s and early 1770s, the two men met and would become friends. In January 2017 I was lucky enough to be a Visiting Fellow at the Moore Institute at my own alma mater, NUI Galway, where I spent time working on a study of the relationship between these two men, examining the ways in which they negotiated their divergent understandings of the Gaelic past at a time when the nature of Gaelic society and literature was, on account of the Ossianic controversy, the focus of much external scrutiny.

By looking at the various literary texts that the men exchanged, I gained an insight into how they sought to present divergent versions of the Gaelic past in an attempt to communicate it to the future. Their different scholarly interests and cultural agendas reflect the circumstances of Gaelic culture in both countries. The Catholic O’Conor, seeking to promote pre-Christian Ireland as a model of good governance, emphasised the centrality and seniority of Ireland within the Gaelic tradition. In doing so he was also driving a contemporary political agenda, one which sought to alleviate the civic situation of Irish Catholics. For McLagan, the focus was on Scottish Gaelic as a contemporary reflex an ancient Gaelic literary tradition, one which he believed had the potential to lift the spirit of a shattered people. The Moore Institute Visiting Fellowship was the perfect way to develop this research. As well as finishing an article on the relationship between these two scholars, I had the time and intellectual space to think about future research plans. I’ve since been invited to participate in a plenary panel at the World Congress of Scottish Literatures in Vancouver in June where, alongside colleagues from Glasgow University, I’ll be presenting many of the ideas I got to develop and think through in Galway during conversations with members of Galway’s scholarly community across a range of disciplines

Peadar Ó'Muircheartaigh

Dr Peadar Ó Muircheartaigh is Lecturer in Celtic Studies at Aberystwyth University, Wales. A graduate of NUI Galway (BA Modern Irish, MA Old and Middle Irish), he has previously held a Government of Ireland Graduate Fellowship in Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame and the National University of Ireland Travelling Studentship in Celtic Studies at the University of Edinburgh. His doctoral dissertation received the Johann Kasper Zeuß Prize of the Societas Celtologica Europaea in 2016. Peadar was awarded a Moore Institute Visiting Research Fellowship for his research at NUI Galway in January this year.