‘Some unfinished business’: New Zealand, Samoa and the legacy of the Great Flu pandemic of 1918

This blog is co-authored by Gavan Duffy and Gearóid Barry.

New Zealand’s handling of the current Covid-19 pandemic has, to date, attracted much positive commentary, with a considerably better record than Ireland, for example, taking our similar-sized populations and island situation into account. New Zealand’s experience in 1918–1919 was not as commendable, especially when it came to Samoa, or German Samoa as it had been from 1900–1914, an island of about 4% of the size of Ireland about 3,000km distant from New Zealand which had been occupied by the Kiwis on behalf of the British Empire in September 1914, displacing the German administration with little bloodshed. The story provides a reminder of lasting legacies that a pandemic can leave in the relationship between two neighbouring island nations where the larger island controls the smaller one in the name of the British Empire.

New Zealand, as a British settler colony, and (Western) Samoa (whose 40,000-strong population was comprised of a mixture of Polynesians and Europeans) became linked, whether they liked it or not, by imperialism and the experience of pandemic. The H1N1 influenza virus, commonly called the ‘Spanish Flu’, was highly contagious and life threatening. It traversed the globe during 1918 and 1919 in three waves, an infectious but relatively mild first wave in March–July 1918, the deadly second wave in August–December 1918, and a serious but more moderate third wave in 1919. Would isolated Samoa escape the worst? In late 1918, with the Allies on the cusp of victory in Europe, New Zealand hoped to retain control of the island, with its valuable copra or dried coconut meat exports. However, the way in which the 1918 influenza pandemic arrived in Samoa would colour the Samoan view of the New Zealanders for many years to come.

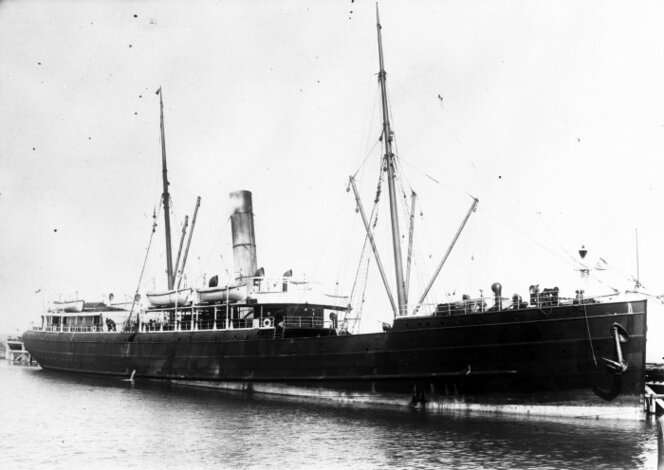

The flu outbreak struck Samoa as part of the global second wave when the steamship SS Talune docked at the port of Apia, the Samoan capital, on 7 November 1918, having sailed from Auckland with sick passengers.

Though the pandemic was at its worst in New Zealand in mid-October 1918, New Zealand officials failed to warn their counterparts in Samoa of the influenza risk. The Principal Medical Officer on Samoa recorded in his diary that ‘it was not until we opened the [news]papers received by the mail brought by the Talune that we learnt there had been an outbreak of a serious nature in Auckland and Suva.’ Public health procedures at Apia port were lax. Talune passenger and missionary Paul Cane, who was extremely sick upon arrival, testified that the official doctor who came on board had failed to carry out any meaningful medical checks on travellers before they disembarked.

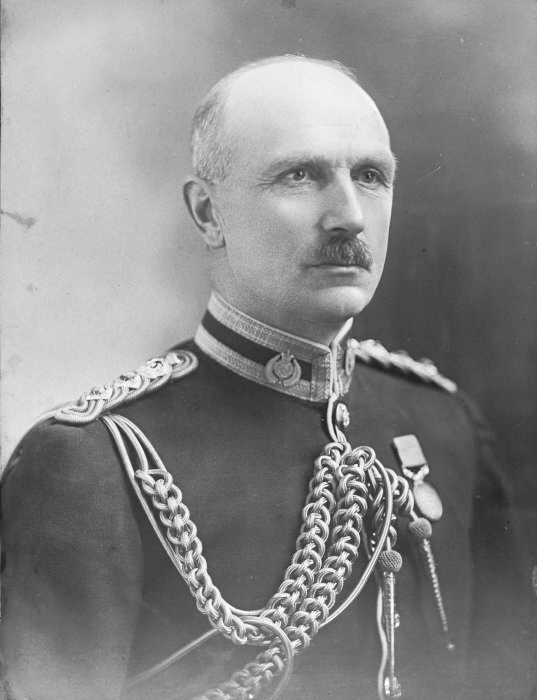

Once Talune passengers had been allowed to go ashore, the disease spread rapidly throughout the island. By 19 November, Colonel Robert Logan, the New Zealand Military Administrator, appealing for help, reported a staggering 80 per cent infection rate amongst the Samoan population. Death abounded. Revealing the dire situation, Logan signalled the administration’s helplessness to his superiors in Auckland, stating that ‘[the] white population has been organised to feed the living and bury the dead around Apia but can do nothing outside.’ On nearby American Samoa – the eastern Samoan islands under the control of the United States – an effective quarantine was put in place and not one case of influenza was reported. Tensions between Logan and the Americans led him to ignore offers of medical assistance and, incredibly, he ordered lines of communication between the two islands to be cut.

Logan’s reputation suffered at home in New Zealand and he was replaced with Robert Tate, a savvier colonial administrator intent on damage limitation. An official New Zealand investigation found that, out of a total population of 38,000, over 7,500 people lost their lives, some 22% of the population. Of the thirty members of the Fono O Faipule, the indigenous advisory council, only six survived the pandemic. Tate remarked in discussions with indigenous Samoan leaders that the flu ‘went through the country like fire through dry grass.’ Wealthy merchant and island grandee O. F. Nelson, a mixed-race Samoan of Swedish heritage, lost his wife, his mother, along with a brother and a sister, all in the space of one week during late 1918.

Pandemic or not, Great Power politics ground on and, following on from the Treaty of Versailles (1919), Samoa was indeed placed under Kiwi administration, though parts of the Samoan elite appealed, after the flu, to be put under British or American control instead. Independence for ex-German colonies like Samoa was not even considered but instead it, and other far-flung territories, were given as mandates to Allied powers, albeit under the mantle of the new world-body the League of Nations, forerunner of today’s UN, as a ‘sacred trust of civilization’.

A proud people, with some local political structures in place, the Samoans did not forget the events of 1918 but accepted Kiwi control for now while using Geneva – headquarters of the League – as a place to air grievances. These evolved, and by the mid 1920s a non-violent movement for Samoan independence called the Mau emerged, with figures like Nelson as leaders. New Zealander suppression of the movement culminated in Black Saturday in 1929 when 11 Samoan demonstrators were shot dead in the capital Apia. Samoa finally achieved independence in 1962. Clearly the incompetence of the NZ administration in 1918 cast a long shadow. In 2002 the then New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark stated during a visit to Samoa that she had ‘been troubled by some unfinished business.’ This business was how New Zealand handled that 1918 influenza and was the result of what she called the ‘inept and incompetent early administration of Samoa by New Zealand.’

Today’s independent Samoa, having commemorated the centenary of its national tragedy in 2018, wants no repeat. In March 2020, it declared a state of emergency, closing its borders to all but returning citizens. Its response has not been without controversy, with its refusal to allow entry into the country of eight of its citizens over coronavirus fears being criticised as a violation of international law. To date, Samoa has not had any confirmed cases of Covid-19 and maintains a national state of emergency. The lesson seems to be: ‘better to be safe than sorry.’

Authors

Dr Gavan Duffy was conferred in June 2020 with a PhD in History examining the origins of the League of Nations Mandates system and its attempted international oversight of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand’s mandates to govern former German colonies in the southern hemisphere in the aftermath of the First World War. A contribution from him on labour in the southern Mandates shall appear in a forthcoming edited volume with Routledge entitled A Century of Internationalisms: The Promise and Legacies of the League of Nations.

Dr Gearóid Barry is a lecturer in Modern European History at NUI Galway, specializing in French history and the First World War. His monograph The Disarmament of Hatred (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) was awarded the Scott Bills Memorial Prize for best first book by the American Peace History (2015). He is currently editing, with Róisín Healy, a volume on Family Histories of World War II: Survivors and Descendants, forthcoming with Bloomsbury Academic.