Africa and ‘Blackness’ in the Irish Imagination

Widespread protests following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis have generated new awareness of historically sanctioned racism that shapes the lives of people of colour in the USA and in other countries around the world. Here in Ireland the issue of racism is also being discussed. A large part of the debate has centred on the treatment of asylum seekers in Direct Provision centres, but we have also seen an outpouring of stories of personal experiences from Black and mixed-race people of all ages, indicating that Ireland is not immune to racism.

Many of these individuals were born in Ireland and recount repeated episodes of abuse, exclusion, bullying, and disrespect from childhood onwards, including discrimination in the workplace. The response to these accounts, shared on social media and on radio, has been one of shock and revulsion, along with surprise that there is racism in Ireland.

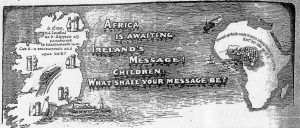

The history of racism in the country, specifically negative attitudes towards Africa, Africans, and ‘Blackness’, can be linked to the Irish missionary movement in the twentieth century, which consistently emphasised the inferiority and savagery of the African ‘Other’. From the 1920s to the 1960s, missionary organisations promoted their efforts to convert the ‘pagans’ on the African continent, using language that was both emotive and disparaging. Individual missionaries may have been well-meaning and selfless in their motivation, but the overall impact of their discourse was to establish Africa in the Irish imagination as a place of darkness, lacking culture and civilisation. My PhD research studied missionary magazines and other popular missionary texts. I never ceased to be shocked by how explicitly racist the material was, and still is.

It’s important to note that Irish missionaries didn’t invent these ideas about the inferiority of other races, but that they exploited an existing discourse for their own ends. Rather than deconstruct existing racist attitudes implicit in imperial discourse, they embraced and adapted them to justify the project of converting the pagan. Due to the timing of Irish involvement in Foreign Missions, and the success and longevity of the missionary project, these ideas lasted well into the twentieth century, and I would argue, continue to structure the Irish relationship with the African continent today.

Foreign missions presented the opportunity for the Irish, who had long been the uncivilized ‘other’ to England, to divest themselves of perceived inferiority and to define themselves as the privileged partner in the relationship with the African. This prospect, allied with the need to justify the process of conversion, allowed for particularly negative stereotyping of Africans. Abdul JanMohamed has described this ‘Manichean Allegory’, in which a non-negotiable opposition between civilized self and uncivilized other is created. Such constructed oppositions are fundamental to colonial discourses, which explain colonialism in terms of the ‘duty’ of the more developed peoples to civilize the savage. Ireland’s spiritual empire may have differed in significant ways from other imperial projects, but it shared some of the same foundational beliefs, including the assumption of the inferiority of the ‘Other’, considered to be, as Kipling’s poem ‘The White Man’s Burden’ describes, ‘Half devil and half child’.

A statement in the editorial pages of Missionary Annals in 1930 promoted equality by maintaining that ‘every soul, whether its envelope of clay be black, white or yellow, has an eternal value and was paid for by the Priceless Blood of Christ’, but the issue of skin colour for Irish missionaries was very complex. Skin colour had long been accepted as the main marker of racial difference; the white skin of the Irish had complicated their classification within the racial hierarchies which emerged during the Victorian era. Charles Kingsley had been confused by what he described as the ‘white chimpanzees’ he encountered in Ireland in 1860. Whiteness was particularly important in the scheme of ‘self and other’ in the context of the missions, where the darkness of skin was often equated to the darkness of sin and ignorance; bringing light to the darkness was a stated aim of the missionaries.

In 1956, in the children’s magazine, The Missionary Junior, a photograph of three black babies was captioned reassuringly: ‘Their souls are white’. The missionary project proposed that black skin might not be yoked to sin and immorality, and that a black person could at least metaphorically be washed white; but the opposite possibility – the danger of contamination – had also to be acknowledged. The missionary who ‘went native’ was rejected by the Church and by Irish society, as depicted by the character Father Jack in Brian Friel’s play Dancing at Lughnasa. Cultural exchange was not a consideration; the aim, as explained on the Children’s Page of a missionary magazine in 1927, was to make ‘poor abandoned Africa a Holy Ireland beyond the seas’.

In an apostolic letter, Maximum Illud (1922), Pope Benedict XV highlighted the African’s potential for development, saying: ‘We can see that backward races are capable of development, and that the time is coming when we must receive them and treat them as equals’. But in a 1927 article on ‘African Morality’, Padraig O’Cullen alleges an African history of ‘internecine tribal strife, slave raiding, and wholesale massacres’, claiming that this past has led to the current savage state of existence and implying that this history has somehow formed and is embedded in the African psyche. The missionaries explained the poor moral standards they perceived as being due to the absence of any framework of civilized society. The complex cultural and historical aspects of social organization in traditional societies were generally unrecognized – and certainly unacknowledged – as was the devastation caused by the missionaries’ activities. One missionary admitted that before he went to Africa, he expected ‘a land where the dread spectres of disease and death stalk hand in hand amongst rude repellent hordes of unintelligent savages’. In this case he pointed out that his expectations were wrong, but if he, who had spent a number of years training to be a missionary, held these beliefs, then what hope was there for the ordinary member of the public, whose main information would have been missionary magazines?

Some of these sources made a variety of insinuations implying that native populations possessed animal-like characteristics: for example, the use of verbs usually associated with animals, including swarming, scurrying, and flocking, in describing the movement of people. The suggestion that the people need to be ‘tamed’ is another example of the use of language more normally associated with wild animals. (Similar language was used in relation to the Irish a century earlier by the Proselytisers, who offered soup in return for conversion.) Indigenous people were also frequently described as childlike. Although the focus of Irish children was directed towards saving the ‘black babies’, it was also suggested that the adult African was more like an Irish child than an Irish adult. In fundraising appeals to train Catechists, readers were urged to ‘ADOPT one … You can have one all of your own; there are Patricks and Columbs and Malachys and Ciarans and Eoins – lots to choose from’.

Irish children were encouraged to spend half-a-crown on the “purchase” of a little black baby and ‘snatch them from the claws of the devil’. Buying Black Babies was a widespread and popular occupation. Cards were distributed by magazines and in schools. Variations on the same theme resulted in the purchase, and power to name, a ‘Black Baby’. Each child (or indeed adult) had a card with printed spots to be punched and in the middle of the card was a picture of an African child. For each penny collected, one of the spots would be punched and when thirty pennies were collected a baby could be adopted. This was a widespread and, in retrospect, highly disturbing element of missionary fundraising. Letters from children, sending money for the purchase of other Black children, were often published, such as this one from the African Rosary magazine in 1936:

Dear Sister,

Will you please buy 4 black babies for my class. We had not time to collect for one each, so some of us are sharing babies. These are the names: Maeve Breen, 1 baby called Angela; Betty Murray and Mary Monaghan, 1 baby named Marie Therese; Madeline Kelly, Betty McEvoy and Sophie Coffey, 1 baby called Magdalen; 1st year C, 1 baby called Mary Ursula.

From the 1st Year C

The naming of these babies was another element of this scheme with imperial overtones; it was an exertion of power, which usurped the parental role and implied control or ownership of these children.

In general, missionaries spoke in condescending terms of the native, assuming their inferiority. A lack of culture and history was assumed, with any evidence to the contrary ignored or rejected. Selective and sensational reporting of customs and practices was intended to create indignation, pity, and horror among the Irish public. What culture was acknowledged in Africa was dismissed as tradition and described as uncivilized; there are tantalising references to ‘dark mysterious rites’ and customs, which are so degraded that ‘details would foul the paper’. Servility and lack of pride were assumed to be innate characteristics.

The shame the missionaries induced in their flocks was both a manifestation of their success and a justification for their presence. Repeated references are made to the capitulation of people who cease to defend their traditions and their separate identity, and who are ‘ashamed of their black skin’. The Africans’ desire for change and the consciousness of their own ‘degradation’ is presented as a spontaneous occurrence; there is no suggestion that this sense of inferiority is due to the missionaries’ repeated criticism of them. Missionaries believed that the pagans were not religiously neutral but rather under the influence of Satan, which is confirmed in the literature by the many references to the darkness in which these benighted people dwelt.

Some of the central themes in the Irish discourse about Africa were the Victorian preoccupations with hygiene and racial hierarchies, which had become established tropes in constructing self and ‘other’ in an opposition of civilized self and savage other. It seems that the Irish Church was quite comfortable using the established language or discourse of colonialism in representing its work in Africa. There is no doubt that the discourse disseminated in missionary magazines, autobiographies, travel writing and other popular reading materials was largely one of propaganda and was due to the necessity of telling superficial, sentimental, and sensational stories to their supporters at home in order to obtain their ‘pennies for the cause’, and to encourage new vocations. Unfortunately it seems that the representations employed for purposes of propaganda came to define the discourse and, more crucially, the attitudes and beliefs of the Irish public regarding the African continent.

There was a gradual change in attitude and approach within the Irish missionary movement that manifested itself from the mid-1960s, and acknowledged the culture and humanity of the African subject, but this occurred at a time when the Foreign missions were waning in popularity, and thus lacked the same authority and impact as the earlier discourse, which was well-established by this point. Although I’m referring to a time when Ireland was a very different place, I would argue that popular ideas and attitudes towards Africa were established during the high point of missionary activity, and that Blackness in the Irish imagination is still bound up with the era of ‘pennies for Black Babies’.

It is evident that many Irish people have been oblivious to the problem of racism in society, and acknowledging the issue is the first step in addressing it. Given how embedded some these ideas and attitudes are, it will take a concerted anti-racism campaign, reaching all levels of society, to counter negative stereotypes and change entrenched attitudes.

Fiona Bateman

Dr. Fiona Bateman is Director of the MA in Public Advocacy & Activism at NUI Galway, based in the Huston School of Film and Digital Media at NUI Galway. She also teaches in the discipline of English. She wrote her PhD thesis on ‘The Spiritual Empire: Irish Catholic Missionary Discourse in the Twentieth Century’ (NUI Galway, 2003), investigating Irish Foreign Missions in the twentieth century and the involvement of Irish missionaries in the Nigeria-Biafra War. She recently published ‘Clarke Studios and the Irish Foreign Missions: Windows with “A very ‘Irish’ Look” in Africa’, in Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State, Angela Griffith, Marguerite Helmers & Roisin Kennedy (eds), Irish Academic Press, 2018.