Remembering the Sun of Joy

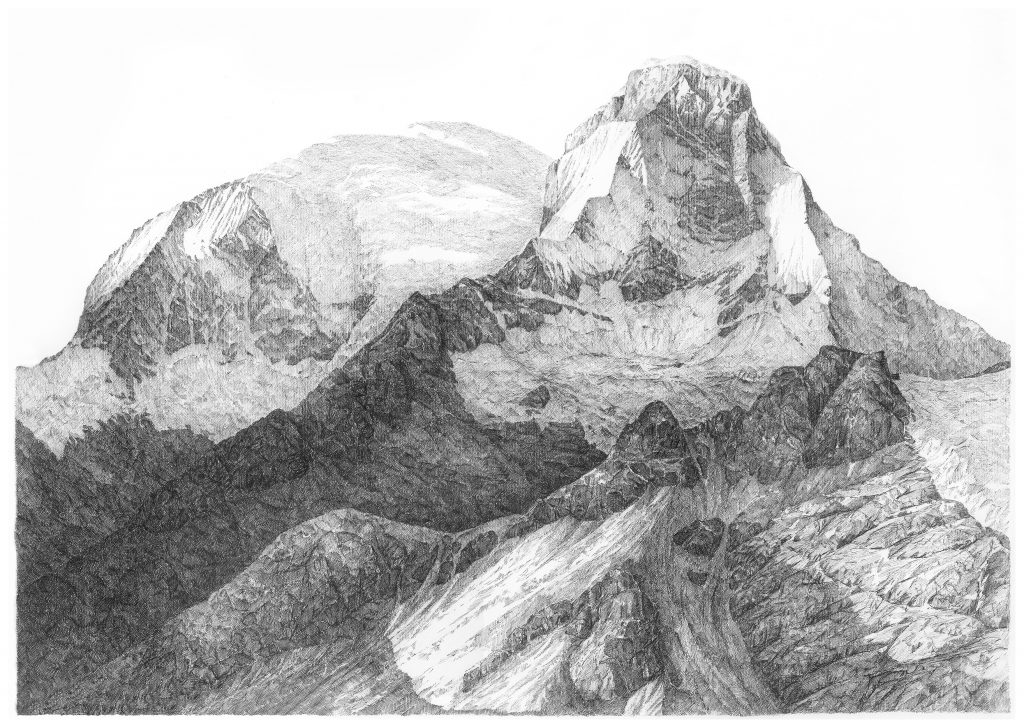

The travellers among us are on short rein this year. Even the most profound distortion of space-time cannot bring the Andes mountains within my personal 5 km radius, and the flat-topped Partry hills of Mayo, visible from our Moycullen garden, remain frustratingly out of reach. So I draw, the practice of art being well known for its meditative and transportive qualities, its ability to wrestle a space into the fabric of daily life where one can nurture that relationship between artist and subject. And it is an intimate, albeit one-sided, relationship. Beside me in this cluttered little room serving as the Home Office, with its sweeping vista of our barn and the impenetrable hazel scrub beyond, is the largest ink drawing I’ve yet done: an 60 cm by 45 cm scene of Peru’s monumental Huascarán massif in the Cordillera Blanca, seen at dawn from our vantage on the icy south slopes of Pisco.

The travellers among us are on short rein this year. Even the most profound distortion of space-time cannot bring the Andes mountains within my personal 5 km radius, and the flat-topped Partry hills of Mayo, visible from our Moycullen garden, remain frustratingly out of reach. So I draw, the practice of art being well known for its meditative and transportive qualities, its ability to wrestle a space into the fabric of daily life where one can nurture that relationship between artist and subject. And it is an intimate, albeit one-sided, relationship. Beside me in this cluttered little room serving as the Home Office, with its sweeping vista of our barn and the impenetrable hazel scrub beyond, is the largest ink drawing I’ve yet done: an 60 cm by 45 cm scene of Peru’s monumental Huascarán massif in the Cordillera Blanca, seen at dawn from our vantage on the icy south slopes of Pisco.

A geologically young fragment of granite and ice jutting almost seven kilometres into the sky, Huascarán is named for (deep breath) Inti Cusi Huallpa Huáscar, the ‘Sun of Joy’, heir to the Inca empire who died by the hand of his jealous brother, Atahualpa, in 1532. The victorious Atahualpa got his comeuppance the following year, however, when he was captured and executed by Francisco Pizarro on the 29th August 1533 during a pivotal moment in the Spanish conquest. Far above mere humanity, 6768-metre-high Huascarán is also supreme apu (or mountain deity) of Peru, famous not only as the roof of the tropics but also for its murderous tendency to unleash muddy avalanches onto the towns below with devastating consequences. Now, Huascarán sits on the office floor, propped against a bookshelf, a little warped by humidity along its top edge and naked of its frame since the Great Mould Scare of February 2020. Yet, even in this inglorious position, it exudes significance for me like a garden wall re-radiating the sun’s heat on a summer night. Because art is evocative, particularly for the artist, and this 2D monochrome representation of a tectonic masterpiece conveys me to two equally valuable destinations that could not be more different.

One of these, naturally, is the cordillera itself, where, for one glorious fortnight in 2011, many of the finer things in life – mountains, friendship, science, curry – coincided to underscore the pure joy of being alive and young. It might sound imprudent now, but there is a selfish pleasure in knowing that, for a limited time, not a single soul on Earth knows your whereabouts or can share what your eye sees. My eyes saw a sky so filled with foreign stars it was never truly dark, avalanches tumbling from hanging glaciers, the pinprick glimmer of climbers’ headtorches on the neighbouring peaks, and the charmless depths of crevasses. Formative as that experience was, it is not to Peru however but to North America that I take you now.

New York, 2011. I was a postdoctoral fellow at a prominent institution just across the river from New York City. This is a landscape of dense vegetation slashed by intense urbanisation, populated with expensive mansions, leased BMWs, and sunbathing rat snakes, all crushed under the weight of a summertime atmosphere laden with heat and thick humidity. Indoors, mass spectrometers hum and click, pouring federally funded data into the hands of some of the brightest minds in our field, enabling us to probe the secrets of our planet and its tempestuous climate. A prestigious fellowship in hand, 2011 should have been a heady stepping-stone in my career, yet I hated it. Something didn’t fit and I quickly learnt to recognise the type of person and mentor that I must never become. So challenging was it that I seriously considered quitting science altogether and would have done had it not been for the wise words of a dear friend, who, by happy coincidence, was a fellow postdoc. I owe my career in no small part to that person.

The drawing, Huascarán, dates from then, a tried-and-tested means of escapism at a time when my wife and I couldn’t see a clear path by which to escape New York. The sketch pad was enormous and could only fit the kitchen table, which, with a 1-year-old and a 3-year-old on the loose, was nowhere close to my idea of an artist’s secluded studio. I would draw when I could, a few lines inked during Lola’s nap, some shading of an icy ridge after their bath, which the children took together in generally good humour. With small children, neither time nor space is your own, as many parents must be feeling acutely in the midst of the coronavirus lockdown. Huascarán takes me there, to that kitchen table in New York, to losing myself temporarily in the granite spires of the Cordillera Blanca, to the stomach-churning anxiety about my postdoc that returned when I closed the sketchpad and placed those fine-line pens in the drawer, out of reach of Erik’s destructive hands. It takes me to the bond of teamwork that Mrs. Bromley and I nurtured under the codename ‘Operation Get Out of New York’, a story with a happy ending that must wait for another time. Above all, it is a monochrome reminder for me that this too shall pass, a message we need to repeat today and always, for better or for worse.

The drawing Huascarán took over a year to complete and it wasn’t until a bright winter morning in 2013, sitting at the same kitchen table but now in our northern New England haven, that I initialled the bottom left of the paper and put the pen away for good. By then, the child tyrants of my theoretical artist’s studio had changed immeasurably, as had our situation, but it would be many more years before I could trust them not to mash my pens or turn watercolour paper into expensive paper aeroplanes. When I take the time to think about it (and Lord knows I have the time right now), Huascarán means a great deal to me; I would do well to remember that and to pick it up off the office floor.

Gordon Bromley

Gordon Bromley is a Lecturer in Geography at NUI Galway, where he pursues his research in climate change, glacial geology, and natural history. Gordon also has a lifelong passion for art and has taken advantage of his field work, in far-flung regions including Antarctica and the tropical Andes, to acquire material for ink drawing, painting, and photography. Together, art and science can tell a powerful story of humanity’s place on this dynamic Earth, and in 2018 Gordon launched an exhibition – ‘Art on the Edge’ – at NUI Galway, hosted by the Moore Institute, featuring artwork from his scientific research. For more on his work, see https://www.gordonbromleyartofscience.com/