Australia under COVID-19

In Australia, a lot of things that were of consuming interest a few months ago have disappeared from view. We were almost on the verge of doing something about climate change after the drought and bushfire summer. I hope we don’t lose that inspiration. On the plus side, CO19 has swept away the culture wars and a cynicism about government, at least for a bit. There has been an outbreak of seriousness and attention to evidence.

In Australia, a lot of things that were of consuming interest a few months ago have disappeared from view. We were almost on the verge of doing something about climate change after the drought and bushfire summer. I hope we don’t lose that inspiration. On the plus side, CO19 has swept away the culture wars and a cynicism about government, at least for a bit. There has been an outbreak of seriousness and attention to evidence.

Australia is having a good crisis so far, and is beginning to open up again from a position of strength:

- almost no community infection now for a while

- 7068 total cases (a close to reliable figure because of really extensive testing) about 550 still active and new cases 7–25 a day for 5 weeks, on 19 May 20.

- Total death toll so far of 100, really heavily skewed to over-70s with pre-existing conditions

- Australian population 25 million for reference – a bit bigger than the Netherlands, about the same as Texas or Shanghai.

We have benefited from having a federal system with conservative government among the feds and the five states & 2 territories, fairly evenly split between Labor and the confusingly named Liberals (in fact, the conservatives). The Liberal Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, was coming off a very bad summer where he made a number of errors about the bushfires, so he was not inclined to be overweening in the crisis. This was crucial and out of character. He invited the state premiers into a ‘national cabinet’ to make the decisions consistent but not uniform across the nation. Partisan politics has played a much smaller part than usual, and everyone in power has listened to the medical experts.

There has definitely been a turn to government and away from free market solutions. As is often the case in Australian political history, this has been led by the unlikely side in our two-party system. Since before the last election, the Liberals were even selling ‘Back in Black’ coffee mug in expectation of a promised budget surplus. They took the mug advertisement down on March 7, then Treasurer Frydenberg announced stimulus and job-securing packages of $A 17.8 billion (March 12), $184 billion (March 21), and $130 billion (March 30). The reversal was that quick.

Unions and employer groups worked together to convince the Feds to double the unemployment benefit (which had become disgracefully inadequate due to the usual conservative ‘surely if you are out of work daddy will find a place for you in his company’ dopey assumptions) and a higher job-keeper allowance, to be paid through employers. What happens when this expenditure winds back is the main unknown. No-one else is putting it this way, but it looks to me like a free-range experiment in guaranteed minimum wage, led officially be a bunch of free-marketeers. The economic implications haven’t hit yet, but they could be scary. At least we’re not rumbling into them in a state of chaos, like some larger anglophone nations one could name.

As of this week (May 12), the country is starting to open up again after a relatively mild lock-down with, like New Zealand across the ditch, the virus almost suppressed. It’s anybody’s guess when international travel will re-start, however. My mob, the settler/invader Australians mostly from the British Isles, are keen on the moat (as big as the Pacific on one side). We may keep the drawbridge up until there’s a vaccine. ‘Safety’ has won out over ‘the economy’ in policy and debate so far, but the economic price has scarcely begun to make itself felt.

To make sense of all of this, it helps to have a grasp of how responsibilities are divided between state and national levels of government here, but that’s a long story. The simplest version is that the Feds collect the taxes and attend to the national economy, foreign relations, etc; the States spend the money largely collected by the Feds on health, education, social services, etc. It’s a lot more complicated than that, but it will do. The other thing worth knowing is that Australia is not like the US in that it has always looked to government as a central provider of services and direction. We are not instinctive free marketeers. All this means that the national cabinet has a good combination of push and pull factors to create brokered solutions, at least while good will prevails (and it mostly has).

Two of the most influential Australian books of the 1960s – Donald Horne’s The Lucky Country (1962) and Geoffrey Blainey’s The Tyranny of Distance (1966) – offered phrases that continue to resonate with in this crisis. Horne meant ‘lucky country’ sardonically, but our luck seems to have held again, not least because of the distance. We closed down from the rest of the world just in time to get on top of the virus and were lucky – one serious outbreak could have changed everything. Then our internal distances between cities and between houses in our expansive towns and suburbs made isolation and social distancing feasible, reasonably tolerable, and effective. On top of that it was late summer and autumn, not the flu season. We like to see ourselves as outgoing larrikins, but acting collectively and inclining to obedience have worked better this time.

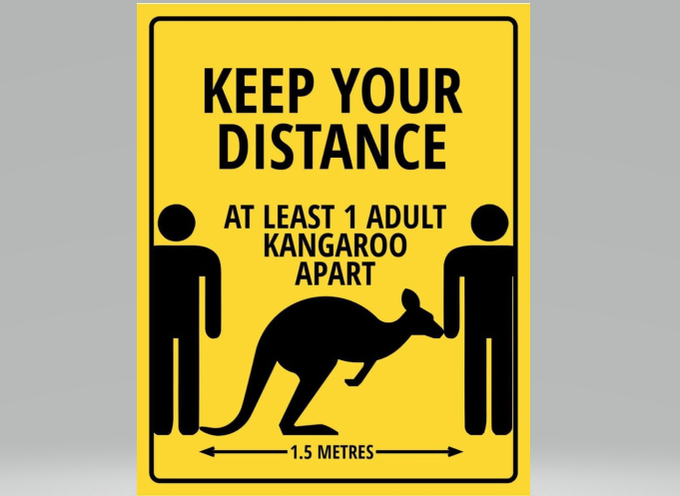

How to accurately social distance in Australia. ???

?: @Dutchie_86 pic.twitter.com/mEZzhWX4dO

— news.com.au (@newscomauHQ) April 18, 2020

I could go on, but will finish with what I think the big interdisciplinary question coming out of all this is: Does this crisis demonstrate the limitations of competition as the all-purpose solution to all questions of policy and service provision? At so many levels, people have leapt to collaboration to address the crisis. It has always been true of universities and the arts, despite the distorting rhetoric of education and creative industries. It has always actually been true in government and, perhaps more often than trumpeted, in commerce. Perhaps we need to stumble into a world post-covid where, within and between nations, collaboration rather than competition becomes the main driver of coping with the planet’s problems. Why not try to imagine it?

Robert Phiddian

Robert Phiddian is professor of English at Flinders University in South Australia. He is a Swift scholar by training and most recently author of Satire and the Public Emotions Cambridge UP, 2019).