Reeling in the years: why 664 AD was a terrible year in Ireland

Analysis: the plague of 664 AD was one of the transformative events of early Irish history and its devastating effects lingered for several years

Analysis: the plague of 664 AD was one of the transformative events of early Irish history and its devastating effects lingered for several years

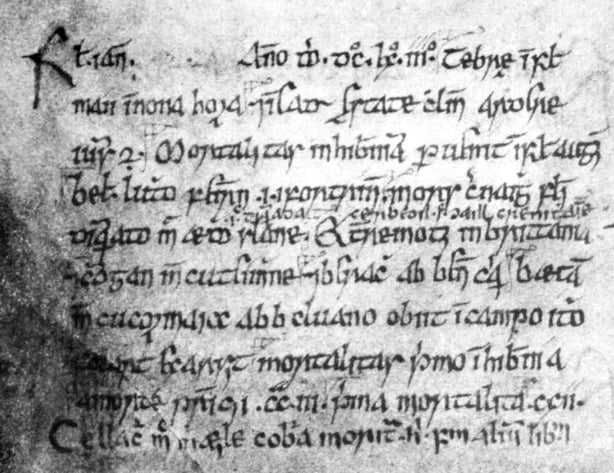

The Irish annals for 664 AD have an ominous entry: “the plague reached Ireland on the 1st of August” (Mortalitas in Hiberniam peruenit in Kl. Augusti). The similarity with our current woes does not end there as the 664 AD was a true annus horribilis.

The opening entry for that year in the Annals of Ulster and Tigernach recorded “Darkness on the 1st of May” (Tenebrae in Kl. Maii). We know that there was indeed a near-total solar eclipse visible over Ireland and Britain of magnitude .94 on that day (in nona hora, “in the ninth hour” says the annalist, with admirable precision). The effect of such a total eclipse on the populations of the two islands can well be imagined. Was it a portent of disaster? The same annalist closed his entry for the year with the statement that “the plague first raged in the Plain of Ith of the Fothairt” (present-day Carlow-Kildare) and was being described as a mortalitas magna (“the great mortality”) by the beginning of the following year.

In fact, we know more about the effects of that plague than we do about most other such catastrophes in the Early Middle Ages such as the so-called Plague of Justinian of the mid-sixth century, which was a real pandemic. Our principal source of information is the famous English historian, the Venerable Bede, whose Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) was published in 731 AD. Bede’s History is more than just a narrow account of English ecclesiastical affairs and is an invaluable source for the political developments that took place in these islands during the years that have been described as “The First Century of Anglo-Irish Relations”.

Bede was very well informed about the entire chapter of Irish history that spans the period from the exile of St Colm Cille from Ireland in 563 AD and his foundation of the famous island monastery of Iona, off the western coast of Scotland, down to the decades of his own lifetime (Bede died in 735 AD). In fact, Bede is our principal (almost our only) source for the second phase of “The Expansion of Irish Christianity” (Colm Cille’s career being the first) that saw Irish missionary monks from Iona take up residence in the island monastery of Lindisfarne, off the north-eastern coast of England, in 634 AD, spreading the gospel there and throughout England in the years and decades that followed.

So profound was the monks’ influence that one modern English scholar has stated that the Church in the north of England was, in effect, a branch office of the Irish Church for the generation between 634 AD and 664 AD. Students of English history remember the year 664 AD as the year of the famous Synod of Whitby, at which (so Bede tells us) the “native” Anglo-Saxon membership of the Church in northern England decided to part company with their Irish teachers and mentors and “go solo”.

In 700 AD, the annals report an outbreak of famine and pestilence in Ireland which lasted for three years, “so that man ate man”

In addition to everything else, the Annals of Ulster record an earthquake in Britain in 664 AD (terremotus in Brittania) and the effects of the decision at Whitby could almost be described in those terms. One consequence that we know of is that the Irish members of the Lindisfarne community (as well as 30 of the English monks who were also in the monastery, according to Bede) decided to leave England and return to Ireland.

After a short period spent on Iona (for de-briefing, no doubt!) they continued back to Ireland, where the leader of the group, Bishop Colmán of Lindisfarne, established the island monastery of Inisbofin, off the coast of Co. Mayo, for them. Unhappy with the conditions that they faced there (per Bede again), the Englishmen in the Inisbofin community demanded a site of their own so Colman established them in the monastery of Mayo Abbey (present-day Baal), which subsequently became famous as “Mayo of the Saxons” (Maigh Eo na Sacsan).

Bede knew enough about Mayo to be able to recount the story of its foundation and explain the meaning of its Irish name (Mag Eó, “the plain of yew trees”). However, he has much more to say (and appears to have been much better informed) about another community of exiled Anglo-Saxons in the Ireland of that time that occupies a central place in his narrative. That place is Rath Melsigi, which is now Clonmelsh (townland Nurney, Co. Carlow, near that “Plain of Ith of the Fothairt”) and it’s where the annals identified as the first place where the plague appeared in 664 AD.

The principal figure in the history of that place, Ecgberct, has been described by some English historians as the “hero” of Bede’s History. His career was indeed a remarkable one, and the story of Rath Melsigi is one that took on an European-wide significance and importance.

The story of Ecgberct and his community takes us back to that fateful year of 664 AD. Bede has a remarkable story about how Ecgberct and his English companions in Rath Melsigi (some of whom he identifies by name) were laid low by the great plague and several were lost to the effects of the virus. While stretched on his death-bed, Ecgberct made a vow (vovit etiam votum) that he would impose a permanent exile on himself and never return to his native island should he be spared the ultimate end. He would instead devote the rest of his days to spreading the gospel amongst his fellow Saxons on the continent.

Ecgberct was spared, as was another of his companions, who subsequently became a bishop in the north of England, and from whom Bede most likely heard the story. Ecgberct’s subsequent career, until his death in 729 AD (aged 90!), are the subject of several other chapters in Bede’s History and he also figures in native Irish sources. The turning-point in his life clearly was his miraculous survival in the plague year of 664 AD.

The plague of 664 AD was undoubtedly one of the transformative events of Irish history in the Early Middle Ages and its devastating effects lingered for several years. Sadly, it was not to be the only such cataclysm that struck here in the seventh century (otherwise regarded as a high-point in the cultural and literary history of the island). The Annals of Ulster in 683 AD report “the beginning of the mortality of young people” (mortalitas puerorum), which it narrowed down to the month of October. By the beginning of the next year, it had become a plague on children (mortalitas parvulorum).

In 700 AD, the annals report an outbreak of famine and pestilence (fama et pestilentia) in Ireland which lasted for three years, “so that man ate man” (ut homo comederet hominem). This was in addition to something akin to foot-and-mouth disease (bovina mortalitas). Hopefully, the efforts of our governments and health authorities, as well as the famous saint of Gartan and Iona, will be a protection to us from any recurrence of such gruesome times.

Dáibhí O Croinin

Daibhi O Croinn is Emeritus Professor of history at NUI Galway. Daibhi is a noted authority on Hiberno-Latin texts, particularly eminent for his significant mid-1980s discovery in a manuscript in Padua of the "lost" Irish 84-year Easter table. He is also a member of the Royal Irish Academy.